What Pulse MDM Learned From Medical Device Experts This Month

Listening to a seasoned and successful Medical Device Sales Rep . . .

Here’s what we learned:

1. Avoid the “Spray and Pray” approach

2. Avoid Resource Dumping

3. Don’t Disrespect Time

Today, we arrive at the fourth and final installment of our series that aims to answer the question, “Do all medical demonstration models need to represent anatomy?” (Spoiler: The answer is no).

In the first three articles of the series, we discussed how and why device replicas are used, how medical skills training can be turned into a game, and whisked you away to a fictional land called Devicia to shed some light on an important training and demo opportunity.

Today, we return from Devicia back to the homeland to wrap the series up by conveying how certain models are built to display the effectiveness of medical devices without the need to imitate the anatomy they are used for in practice.

Devices like the ones we will highlight below help medical device companies demonstrate the amazing attributes of their products as they perform their intended tasks. The goal of these device manufacturers in these instances is to create a medium to train and demonstrate their devices in a way that will optimize skill acquisition and visualization of the intended task without the need to make that medium closely align with the human anatomy it will be performed on clinically.

As we have talked about in previous newsletters, portability and convenience is a key part of what we do. From the viewpoint of a medical salesperson or trainer, a product that can’t be demonstrated or trained to its full potential is a product that is more difficult to sell.

As discussed in part one of this series, there are numerous instances where a product needs to be scaled in a way that allows it to be more easily transported or demonstrated than the actual product would allow for. Sometimes this means scaling a very large product down or only including the necessary components for demonstration or training. Other times, this means creating a replica of a product that allows for a more convenient visualization of its functionality.

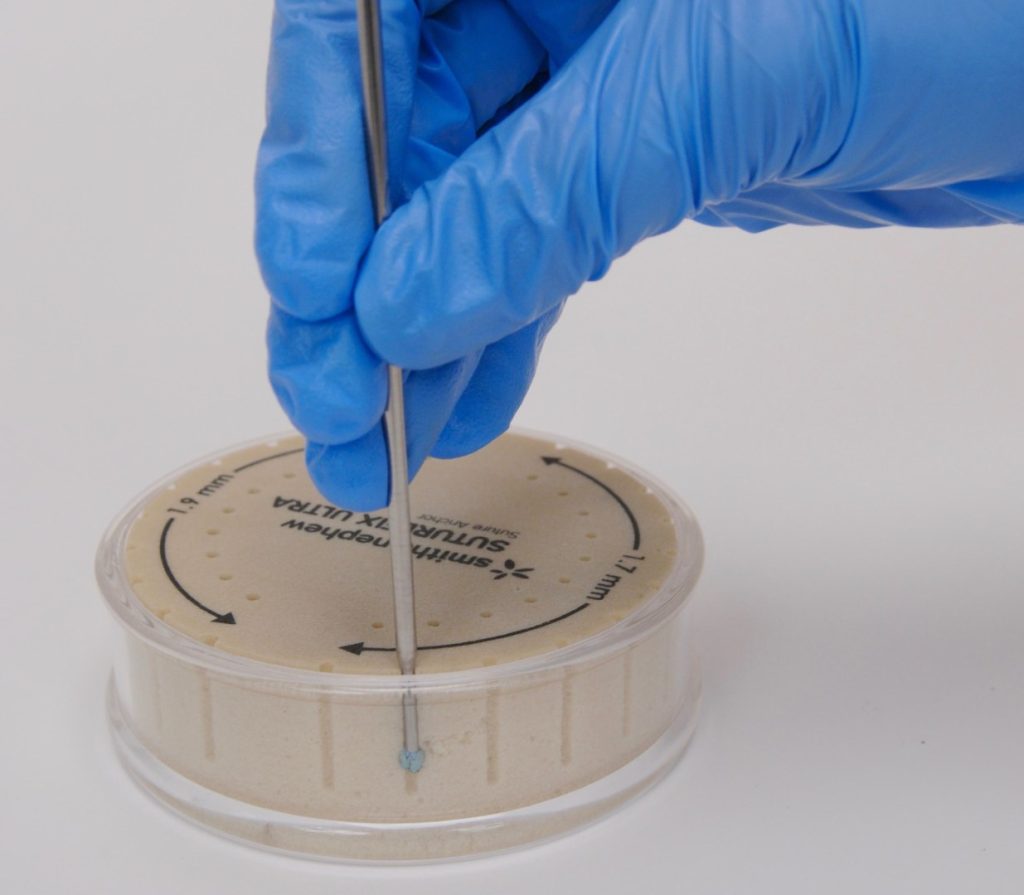

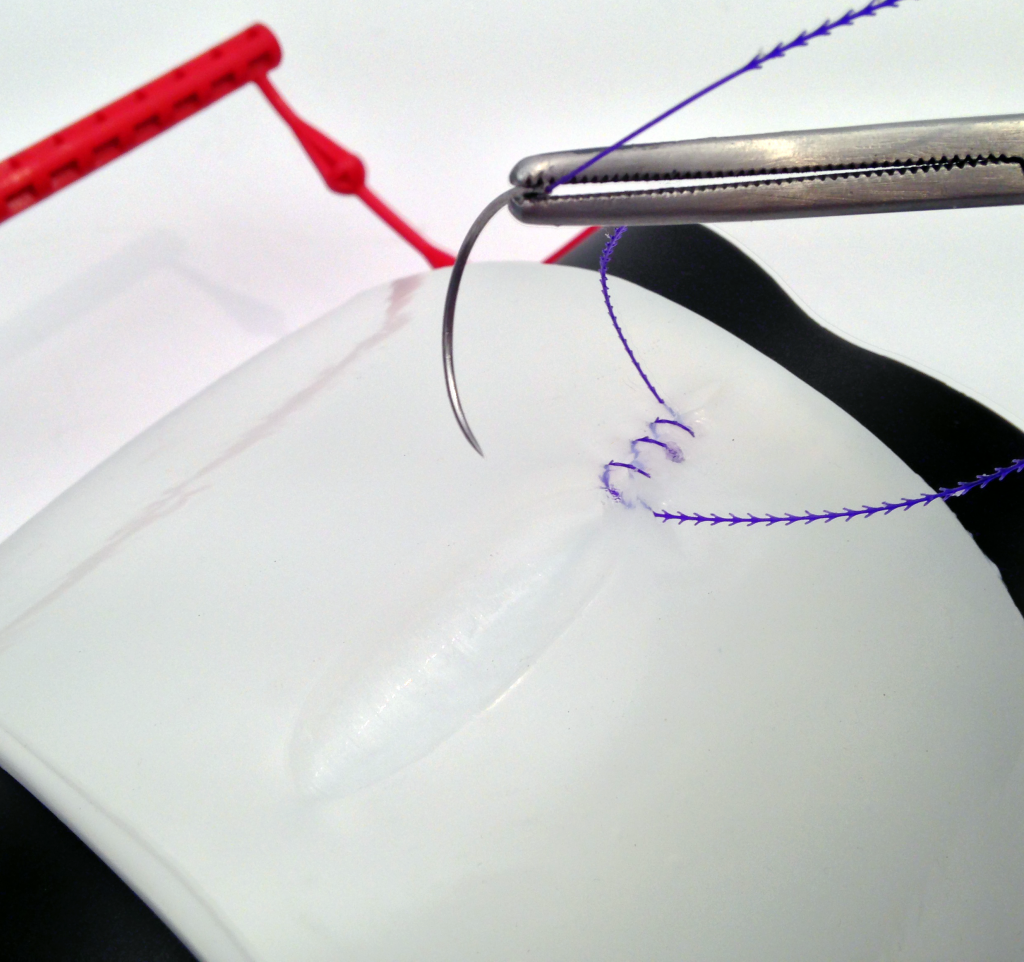

An example that touches on both aspects is a replica we created for a Smith & Nephew product called the Suturefix Ultra. This product is an all-suture fixation device used primarily during rotator cuff repair and hip/shoulder labral repair procedures to provide a durable and secure anchor while removing less bone than traditional fixation anchors. It also utilizes a click-in-place audio cue for the surgeon to confirm the anchor is set.

The challenge our customer was looking to solve was finding a way to demonstrate the advantages of the Suturefix Ultra in a way that would allow both method-of-action visualization of what was occurring in the patient’s joint during the procedure, as well as testing its hold strength and experiencing the tactile feedback.

For this challenge, the best solution was not to create an anatomical model of the shoulder or hip, as this would have resulted in a few shortcomings:

Instead, we created a compact, portable product composed of two pre-drilled suture deployment hole “rings.” By using a model design that was non-specific to an anatomical structure or joint, the physician was able to envision the device being utilized at any joint.

An anatomical demonstration makes sense for products used to target a specific body structure but would have limited the scope of this particular device. Additionally, the model was designed to allow for many (36 to be exact) practice sites, which resulted in the need for drastically fewer demo models.

The outside holes in the bone block were open on the side that is up against the outer clear sleeve and provided excellent visibility of the mechanisms of the Suturefix Ultra using what we call the “ant farm” approach. The inside ring of holes was fully within the bone block and provided a secure anchor point for surgeons to conduct their own anchor pull test so they could feel the security they expected from the Suturefix anchor. This allowed for the best of both worlds in a convenient package.

Building a model that enhanced visualization, increased demonstration and practice applicability, and provided audio and tactile cues significantly augmented the ability to demonstrate the product’s effectiveness through the incorporation of multiple senses. Incorporating more sensory cues leads to improved recall and recognition of the product and the processes involved with using the product. This greatly benefits both the salesperson and the surgeon, which trickles down to ultimately improve patient outcomes.

For decades, medical device salespeople have used hollowed-out vegetables to represent internal body cavities. After all, vegetables provide a good deal of variation in size, contours, shapes, and textures. They’re also just…fun. Their vibrant colors and familiar, wholesome aromas are (literally) a breath of fresh air (especially compared to a cadaver).

They also allow for easy visualization and cleanup. However, as you can imagine, durability and reusability are not exactly their strong suits.

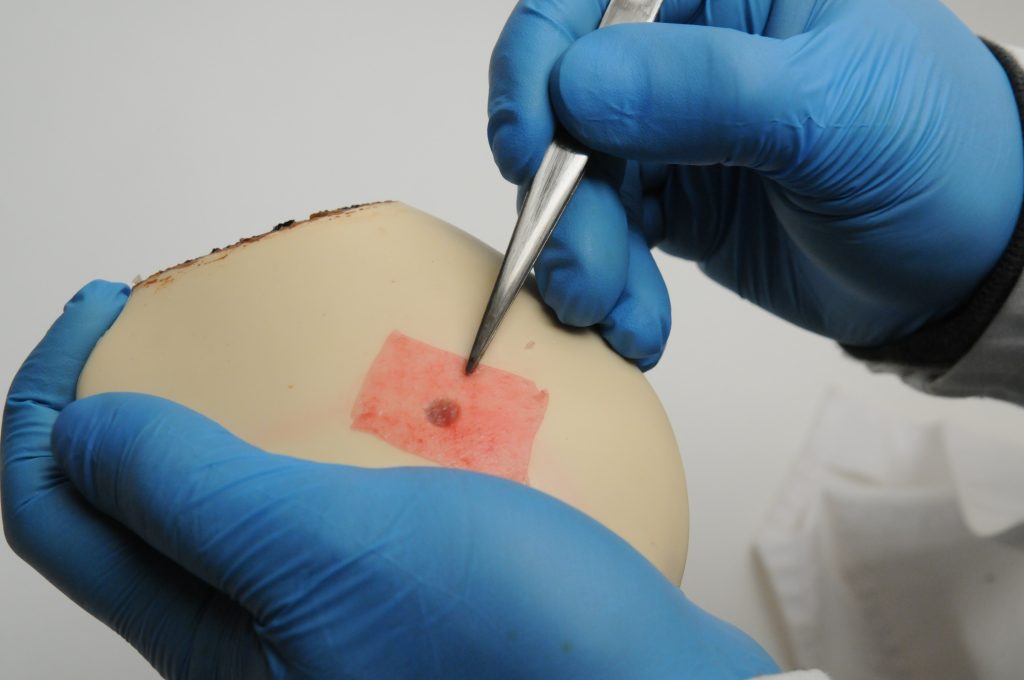

To intertwine the enjoyment and tradition of using a hollowed-out vegetable with the durability and beauty of a custom model, a forward-thinking client said, “Let’s use a pepper for the fun of it but make it into a model so it can be reused.” And with that came the birth of Dr. Pepper.

This Dr. Pepper is not a fizzy, delicious soft drink but rather the perfect blend of function and fun. Just as real peppers have been used in the surgical training space for decades, the purpose of this model is to allow surgeons to practice their wire manipulation skills.

Surgeons love the ability to conveniently hone their skills using a medium that is as playful as it is visually striking. Just as importantly, surgeons tend to be a spirited group of individuals who thrive on self-competition. The Dr. Pepper model addresses this by including a variety of colored dots with tiny entry points, each representing a different level of difficulty. As discussed in part 2 of this series, turning skills training into a game is not only amusing, but it also enhances skill retention and development compared to traditional modes of practice.

Salespeople benefit significantly from these factors because they can provide an experience that is professional and unmistakably memorable using a model that is durable and infinitely reusable. When the customer interaction shifts from a discussion to a hands-on experience, the product sells itself.

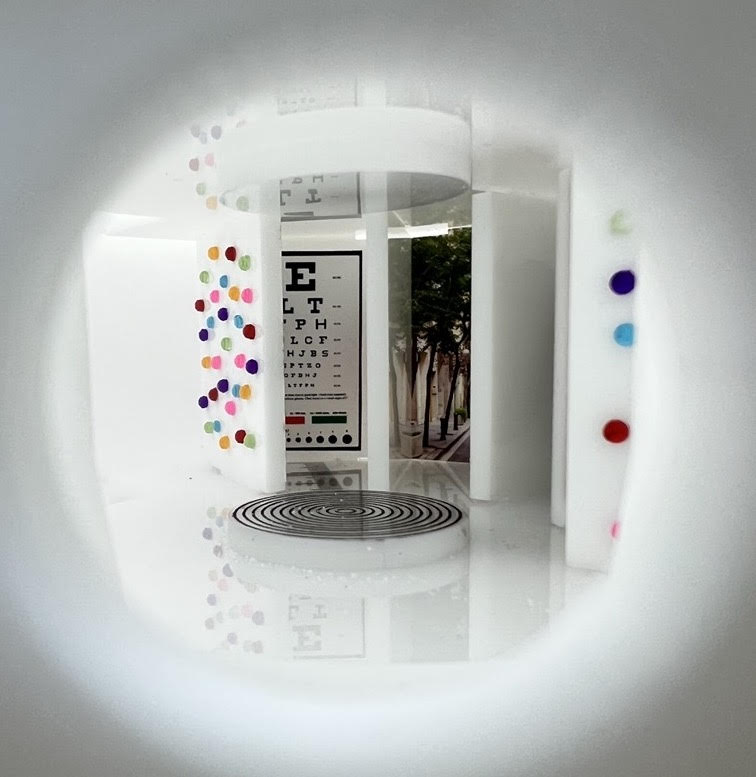

Just as the Dr. Pepper model turns skills training into a game while simultaneously providing a non-anatomical platform for enhanced visualization and surgical skill acquisition, so does The Funhouse.

The Funhouse model was created as a vehicle to show scope illumination, image clarity, and color. But puttering around a basic demonstration using familiar anatomical landmarks doesn’t create as memorable of an experience as something novel and interesting. The consequence of predictability is the risk of getting lost in the noise of the competition or, worse, being bored. Our result is anything but boring.

The Funhouse includes rooms to highlight image contrast, depth of field, clarity of subtle texture using sponge and rock, and the ubiquitous eye chart. What is the smallest lettering you can see?

The model is small, not only for portability but to depict the volume of the body part the scope is intended to explore. This is important, as the engineers designed the light output to specifically match the organ’s volume so that if the model were too small or too large, it would not show off the scope’s performance.

As miraculous as The Funhouse looks from an artistic design perspective, it accomplished its functional goal. It allows clinicians to both experience the clarity of the company’s scope while also sharpening their navigation skills. These skills encompass the same immense precision and awareness needed when they have real patient lives in their hands.

Starting back in August of 2023, we set out to answer a simple question: Do all medical models need to represent anatomy? The answer to that question, in its most condensed form, is no. Medical demonstration models do not always need to represent anatomy to be functional, beautiful, and effective.

In fact, as the numerous examples of this four-part series have made abundantly clear, there are many times when non-anatomical models provide a better experience for both the customer and the salespeople.

The takeaway from all of this is what matters in the end is that an experience is provided. The canvas that experience is painted on won’t always be the same. This variability is the foundation of painting a picture that’s exciting, interesting, unique, and, most importantly, unforgettable.

So, thank you for perusing our medical demonstration model perspectives. We hope each of the four articles provided a different viewpoint and things to consider. And most of all, we hope you gained some valuable insights that you can apply now and in the future.

It’s a magical time of year, and we could all use a little more magic in our lives. If you’ve read the previous two “Ask Allison” posts, you know we have embarked on a four-part series to answer the question, “Do all medical demonstration models need to represent anatomy?” If you didn’t get the chance to check those out yet, you can get up to speed here and here.

As promised, we will continue that adventure today with part three. But today’s story is different. Our story today will allow your creative minds to flourish. It will take you to a world and time far away, yet right where you are here and now. We may all take something different out of the journey we’re about to go on together. Some will simply read an amusing story about magical folks, while others may find a deeper meaning. Let me take you there now…

We begin our story in a distant village called Devicia. The village is, and has always been, an upbeat place with some of the very brightest witches and wizards. In fact, legend has it that Merlin himself spent nearly a decade living here to propel himself to the eventual greatness he would achieve.

Witches and wizards from all over the world travel here each year to discover the best and brightest advancements in wands, potions, and magical gadgets. At nearly every turn in Devicia, you can find a shop that sells these items. Although the shop owners don’t like to admit it, they’re all competitive with one another. This quiet competition is what keeps the village at the cutting edge. Every shop owner bravely attempts to do what has never been done before to stay one step ahead of their neighbor.

As if the long hours of trying to keep their shops ahead isn’t enough, there’s also one other important milestone that must be overcome: receiving the Blessing of the Fortress.

The Fortress of Demons and Angels (better known simply as “The Fortress” by the locals) is the ruling power of Devicia. The members of the governing body that make up the Fortress are known as the Regulators (or “Regs” for short).

The Fortress serves an incredibly vital role in the success of Devicia. You’d be hard-pressed to find a single Devician who thinks otherwise. The Regs work tirelessly to test each and every wand, potion, and magical gadget created here that meets a High-Risk classification to ensure they’re safe and effective for all Devicians and our guests from outside lands.

But the Fortress’s greatest strength for our village is also their greatest weakness. The Regs have extraordinarily strict rules and bylaws to gain the Blessing of the Fortress. Most of the time, this is to the advantage of the Devicians. However, some of these rules and bylaws prevent potentially remarkable potions and gadgets from achieving Blessing in the timeliest manner.

But the shop owners are smart and creative, as are the witches and wizards from Devicia, to whom they sell their magical products. Although the shop owners are bound by the laws of the Fortress, the witches and wizards are lawfully free to use the magical gadgets however they see fit, regardless of the approved use of the gadget received Blessing from the Fortress.

Shop owners started realizing that in special circumstances, a powerful magical product that could create wonderful effects for Devicians may not need to go through the long, arduous Blessing process before it could benefit the wizarding world. After all, talented witches and wizards are free to determine brilliant and creative uses for magical commodities that extend far beyond the approved indications of the Fortress.

Shop owners began creating training tools for how to use their magical gadgets that show possible alternative uses for these gadgets without advertising them. Although no words are spoken, new experiences are realized by the witches and wizards, who can see the true underlying beauty and utility of the magic that lies beneath the surface.

These cleverly crafted experiences are used only for specific goods that are considered an improvement that the Fortress would not require a new Blessing process. They don’t break the rules of the Fortress because the underlying function of the magical products is simply implied by showing the Devician customers rather than telling them. Shop owners are not telling anyone in the village how to use their magical inventions but rather demonstrating that they exist and letting the witches and wizards decide how they are best used for their specific needs.

As an example, a crafty shop owner named Ophelia invented a magical gadget she called The Unbreakable Balloon. Ophelia received approval from the Fortress for the inflation of the Balloon in empty rooms to clean every surface. The product was a huge success with the witches and wizards. However, they wanted to inflate the balloon in rooms without removing the furniture. Eager to satisfy the needs of her customers, Ophelia had some work to do. The current balloon was not compliant enough to conform to all the irregular shapes of the furniture. Have no fear! Ophelia was very clever and added a shape-shifting spell to the balloon, making it more compliant.

The Fortress approved the Unbreakable Balloon to clean empty rooms, not rooms with furniture. In some circumstances, the Fortress does allow for improvements to the approved gadget without a new Blessing process, but changing the indication requires resubmission, which can be a lengthy process.

Ophelia was particularly excited about this gadget and wanted to quickly ensure its improved abilities were portrayed to their full extent without crossing any boundaries of the Fortress’s rules that would classify her improved balloon as a new product.

Ophelia engaged the village builders to assist her in developing creative ways to demonstrate just how useful this new product could be. The builders jumped at the chance to be a part of something so special and began to cleverly craft portable demonstration rooms using Ophelia’s specifications.

These demonstration rooms were nearly as magical as The Unbreakable Balloon itself. The models included complex shapes within the room for the balloon to envelop. They were beautifully designed to make The Unbreakable Balloon an unforgettable product for anyone who got the chance to see how it conformed to complex and protruding surfaces. The rooms were not only visually and functionally appealing, but they could also be shrunk and taken anywhere with the flick of a wand.

Customers were astounded! Many saw The Unbreakable Balloon exactly as it was demonstrated: the perfect house cleaning companion no matter the size, shape, or contents of your room. But others saw a deeper meaning than that. They understood that although The Unbreakable Balloon was being advertised as a house-cleaning tool, it could serve Devicia and all its surrounding lands in wonderful ways. If The Unbreakable Balloon could conform to any room, with or without furniture, and turn it from a disaster to as good as new, just imagine its possibilities outside the home! The magic of this gadget could help the lives of Devicians in endless ways.

As word of this valuable gadget continued to spread around Devicia, The Unbreakable Balloon flew off the shelves. Ophelia had so much demand for the product that she was able to open three more shops and hire saleswizards to travel around the world with her demonstration rooms to introduce the product to new magical communities. The portable demonstration rooms were their greatest tool in allowing The Unbreakable Balloon to practically sell itself.

As it turns out, the model was a priceless tool all over the world as it transcends spoken language. Creative and resourceful witches and wizards all around the world, not just in Devicia, understood the merits of Ophelia’s Balloon. The magic community enjoyed improved outcomes thanks to one product that Ophelia never advertised as anything but a simple house-cleaning gadget.

Now Ophelia is often booked as a keynote speaker to discuss her path to success. She reminds shop owners that customers are not interested in the features or specifications of a product but rather in how the product can help their audience achieve their goals, solve their problems, or improve outcomes.

By showing their fellow Devicians a product and letting them determine what it’s best used for, shop owners can appeal to the customers’ needs rather than focusing on the magical gadget itself. She likes to end her speeches with a quote she learned from the village builders: “If a picture is worth a thousand words, a model is worth a million.”

When it comes down to it, remember that no matter what you sell, the person you’re presenting it to must see its value in their life. A product’s value is internalized by a potential customer much more when they are experiencing something unforgettable versus simply being told of its potential merit.

Sometimes, demonstrating the capabilities of a product allows customers to conclude the product’s best purpose – all by itself – even when no specific use cases are discussed. After all, healthcare practitioners are their own type of magical folk who are even smarter than the shop owners of Devicia.

The ability for clinicians to practice and perfect the skills necessary to enhance and save lives is undeniably crucial. Having the right tools to accomplish that necessity is the first step.

What if those tools are not just effective but also fun, memorable, and engaging? What if they can surprise the user with unexpected challenges that replicate the skills needed for the medical procedure they are preparing to perform? By turning stressful and complex tasks into a game, we can ensure the kind of buy-in and engagement that leads to true internalization of learning.

That’s the power of the “gamification” of skills training. If you read part one of the upcoming four-part series that sets out to answer the question, “Do all medical demonstration models need to represent anatomy?” you already know that there are many times when it is neither necessary nor beneficial to provide anatomical replication when creating the model.

In today’s discussion, we will dive into part two: how gamification can enhance learning outcomes and clinician engagement through multi-sensory, delightful experiences.

Much of what surgeons do requires complex and intricate processes that have very little room for error. If these processes are to be completed at the required level of precision, the surgeon needs to be able to utilize their skills in a way that is nearly automatic. Some would call this “muscle memory,” while others would correctly argue that muscles themselves have no memory.

The automated exactness of these skills is, of course, developed through repetition to the point of being able to visualize each minuscule movement required to complete the task. For this level of learning to occur, the learning process needs to be memorable.

In the same way, that song lyrics are far easier to remember than a verbatim recital of a paragraph from a textbook, medical training processes are easier to remember when the medium used during the training provides higher-level stimulation.

Providing a memorable multi-sensory experience for medical training often does not involve anatomical representation at all, much less a 1:1 replica of the anatomy. Creating a model that will facilitate efficient learning of complex tasks may involve turning that task into a game or otherwise increasing the entertainment factor.

Injecting entertainment value into a novel task or knowledge set has been shown to increase “unique cognitive resources, associate reward, and pleasure with information, and strengthen and broaden memory networks.”1 This is precisely where the “gamification” of skills training comes into play.

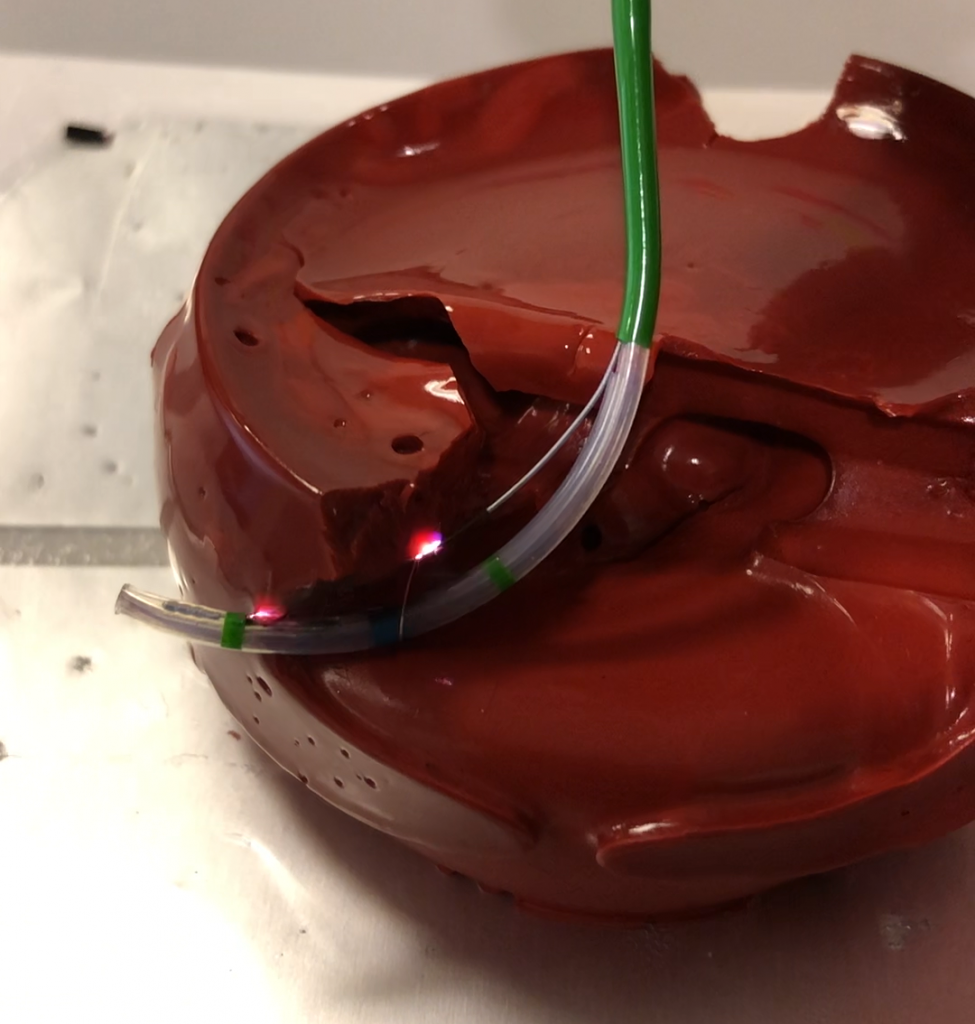

Urologists are an example of specialists who often must perform complex surgical navigation tasks. This can be a high-stakes “maze” of sorts and requires immense precision and control of the scope and surgical apparatuses.

To enhance this important training, we developed a model that requires the same precise navigation as a surgical stone extraction in a beautiful and appealing way without the representation of anatomy.

As you can see with this model, the clinician has the opportunity to complete various pathways that each provide unique challenges and require a specific skill set.

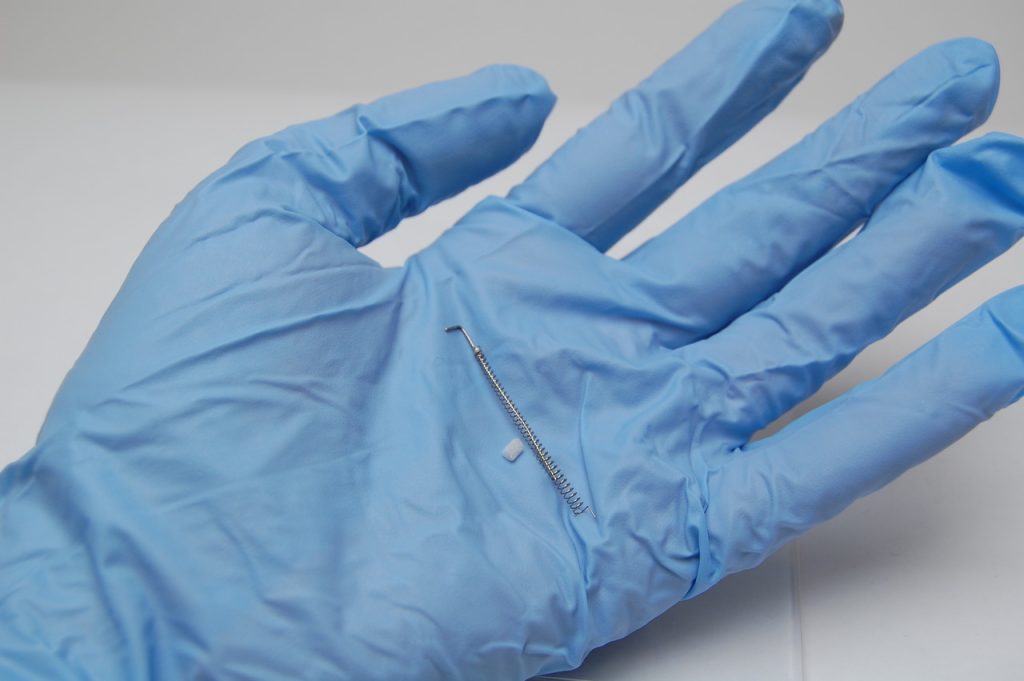

Similarly, we developed a urology obstacle course model that provides an opportunity for surgeons to practice their skills by guiding a wire through a tract. The model’s tract includes built-in detours to create navigation challenges for training kidney stone extraction.

The combination of detours and adjustable tract stricture provides the clinician with the chance to fail. The opportunity to fail is the opportunity to overcome failure and sharpen one’s skills.

Just as a video game captivates players with its intricate mazes and unexpected challenges, these models have a similar effect on surgeons. They transform the learning process into an exciting journey of discovery and mastery, akin to conquering levels in a game. As learners navigate through the model’s complexities, they’re not just acquiring skills; they’re experiencing the thrill of overcoming obstacles, the joy of unexpected victories, and the fun of game-like learning. It turns education into an adventure!

Although the urology examples above highlight the use of non-anatomical models with the primary goal of enhancing the training experience of surgeons, models may also be used by a device manufacturer to demonstrate the performance of their product while providing an unforgettable training experience in the process.

A particularly fun example of this notion was a model we created to demonstrate the clarity of a company’s scope. Instead of exclusively utilizing the typical anatomical models that demonstrate vasculature, tumors, and other standard scope pathways, we decided to turn the experience into something that would be indelible.

By using a demonstration medium that the target audience had never seen, we created an experience they wouldn’t forget. It both demonstrated the clarity of the scope while simultaneously allowing clinicians to practice their navigation skills with the product.

The representation of anatomy is important and imperative in many situations. It is much of what we do here, after all! However, in certain scenarios, not using anatomy creates the most memorable and effective outcomes. A number of those scenarios will be covered in this four-part series that answers the question, “Do all medical demonstration models need to represent anatomy?”

The most entertaining of those scenarios is undoubtedly turning skills training into a game through the use of unforgettable models that do not represent anatomy. The examples covered here today are a nanoscopic sample of the endless possibilities to turn a model into an experience.

It’s a method of learning that brings surprises, challenges, and joy to the clinicians who dedicate their lives to the betterment of others. It’s a way of turning a complex task into a fun and memorable adventure. It’s a way of making skills training not just effective but also enjoyable.

As the late American philosopher John Dewey once said, “All genuine learning comes through experience.” Experiences this unique will not be forgotten.

If you’ve read any of the previous Ask Allison posts, you know that medical demonstration models are made to tell a story. As the name suggests, the stories these models tell involve some component of medicine. This can be anything from a widespread “30,000-foot view” to an intricate detail of a microscopic procedure.

Based on the nature of human medicine, our models often involve some component of anatomical representation. Pulse MDM’s anatomy models provide context for demonstration and training.

However, medical demonstration does not exclusively rely on human anatomy. In fact, in many cases, it may be preferable or even pertinent that anatomy is not included. Today we’ll dive into part one of a four-part series on the most common scenarios where our models don’t represent anatomy and why these instances provide the most compelling stories for our customers.

One of the most common reasons we create device or product replicas for customers is the ability to showcase the features of a device with a much lower price tag than the product itself. It provides a level of protection for the customer by lowering the stakes of the demonstration and training while increasing access to hands-on demonstrations.

One such example of this is an amniotic tissue replica we created for a customer. Products derived from amniotic tissue have some amazing properties that make them a valuable resource in the treatment of chronic wounds.

Amniotic membrane products are derived from human tissue that should not be squandered. They are rigorously processed using sophisticated technologies, leading to a costly and valuable demo if the real product is used. Since large sales teams require a high volume of samples to equip each salesperson, it is not typically feasible to provide these teams with the necessary number of samples.

To maximize sales force efficiency, we manufactured hundreds of amniotic tissue replica samples using non-perishable, non-biologic products and non-medical manufacturing facilities while mimicking the properties of the amniotic membrane for clinically relevant demonstration and training. This kept costs drastically lower for our customers and allowed all their salespeople to provide an unforgettable, hands-on experience for their potential clients.

Another common reason for utilizing device replicas without the inclusion of an anatomical model is that some devices contain tiny, intricate details that are difficult or impossible to see with the plain eye. In these cases, our replicas can be upsized to show the fascinating details that make the device unique.

One such example is a model we made for DePuy Synthes. The model includes an upsized replica of their Fibergraft morsel alongside a vial containing the actual morsels. The Fibergraft morsels are used as bone graph substitutes.

The challenge for the DePuy Synthes sales team was that this astonishing piece of technology would require a microscope for the optimal demonstration. Our replica model solved this issue by showing the detail of the Fibergraft morsels at a much larger scale, which allowed surgeons to physically see the fibers that provide a 3D structure for cell attachment vs. relying on the hands-off video demonstration that many sales teams would use with similar products. While the surgeon is examining the upsized replica, the salesperson explains how the Fibergraft mimics the body’s natural bone healing process without the challenges of allografts.

Replicas like this allow surgeons to experience an “ah ha” moment on their own and understand the brilliance of a product at a deeper level.

As we have talked about in previous newsletters, portability and convenience is a key part of what we do. From the point of view of a medical salesperson or trainer, a product that can’t be demonstrated or trained to its full potential is a product that is more difficult to sell.

In contrast to the previous section, there are numerous instances where a product needs to be made smaller to allow it to be more easily transported or demonstrated than the actual product would allow for. Sometimes this means scaling an exceptionally large product down or only including the necessary components for demonstration or training. Other times, this means creating a replica of a product that allows for a more convenient visualization of its functionality.

One example of a replica we created to improve portability without scaling the product down was for a mobile hemodialysis unit from Outset Medical called TabloCart. The Tablo system is a “dialysis clinic on wheels” and needs only an electrical outlet and tap water to operate.

With any new device, training and demonstration are needed, but the cost of shipping the product to numerous locations was both expensive and unnecessary, given the fact that medical staff would not need every component of the device for training.

To solve this problem while allowing Outset to tell their story, we created a replica of the TabloCart that includes an accordion-style back that can be expanded and locked into place to show the full volume of the cart during demonstration and training but collapsed to a quarter of the volume for shipping and transporting.

Additionally, the replica uses visualization of certain components that are unnecessary for training through two-dimensional images vs. the heavier, more costly, and less durable three-dimensional components.

These creative workarounds allow all necessary training to be completed for operating the device without adding the extra weight that is necessary for a fully operational TabloCart. The replica is an abbreviated version of the product without needing to change its form factor.

The increased portability saves Outset Medical significant money each time they need to ship the product. Increased portability removes the planning required to ship the product ahead of time, allowing for greater flexibility in scheduling. Increased portability allows the salespeople to transport the demo unit themselves without the logistical difficulty of locating a hospital loading dock. Increased portability allows them to do more than one demo a day. Increased portability means more demonstration, which leads to increased adoption. All of this occurs without sacrificing the lasting memorable impact of the device’s convenience and effectiveness.

The final reason we will cover today for the use of replicas without involving a representation of human anatomy is the ability to compare a product against that of a competitor.

Due to procurement challenges and trademark laws, a direct comparison of a competitor’s product against a company’s own product may not be viable. In both cases, utilizing a replica of a device similar to your competitor’s may be the best option for demonstration purposes.

An example of this type of replica was one we created for a Hologic. They wished to showcase their contraceptive solution compared to a competing product.

Their product was a tiny implantable silicone device that created an occlusive barrier of the fallopian tubes bilaterally. The use of a silicone product provided a more comfortable experience for the patient while maintaining a high level of effectiveness without the need for an abdominal incision.

For this purpose, competitors used a nickel-based coil spring with pointy ends. By creating the side-by-side replicas, we were able to help Hologic and their sales team demonstrate a clear advantage in comfort and reliability just by allowing surgeons and patients to see the products together. These visual comparisons transcend any language or communication barriers.

This creates a level of distinction that leaves a lasting impact on the surgeon and the patient.

Representation of anatomy is undoubtedly a crucial part of what we help clients with at Pulse MDM and plays an equally vital role in medical training and sales. However, there are important scenarios in which anatomy is not represented when telling the story that needs to be told.

Today, we dove into this premise through the scope of device replicas. Replicas are an exceptional tool for reducing costs, scaling products to allow for optimal portability and demonstration of features, and allowing side-by-side comparisons against similar products.

As useful as device replicas are, they only represent the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the non-anatomical models we create. In parts two through four of this series, we will delve into even more fascinating uses of non-anatomical models, including FDA compliance (demonstrating functions without breaking the rules), peeling back the anatomy involved in a procedure or process to see the methodologies in action, and the “gamification” of skills trainers (turning medical training into a game).

“Can you make my model clinically accurate?” It’s the one question that we hear more than any other. As simple as the question seems, the answer is the same annoying answer as many others you find in science and medicine: it depends.

The reason the answer is not as straightforward as one may assume is that, although the intent of the customer asking the question is never to be ambiguous, the question itself is indeed ambiguous.

“Clinically accurate” refers to the degree of precision of the model. A clinically accurate model would be created to look, feel, and act as close to real human tissue as possible, down to the cellular level.

Depending on what you’re using as your sample, clinical accuracy can be achieved with a high degree of time and resources, but even with these variables in place, it is still nearly impossible to define in the context of anatomy. As you all know, there are infinite variations in human anatomy, and within any anatomical structure, there are numerous layers of tissue, all with their own individual composition.

What is a clinically accurate depiction of one person may be largely inaccurate for another. There is beauty in the endless uniqueness of our species, but it solidifies the fact that there truly can’t be a decidedly clinically accurate model that encompasses humans as a whole.

In almost all instances, the intent of the question is actually, “Can you make my model clinically relevant?” The answer to that is a resounding yes!

Clinically relevant refers to the degree of usefulness of the model. And the degree of that relevance can be as intricate as necessary for the model to tell the story that the customer needs it to tell.

As was discussed in our March issue, our models are made to tell a story. The story they tell comes down to what message needs to be conveyed by the customer. Will their model be used for patient demonstration of anatomy or a physiologic process? Will it be used to train surgeons on a new procedure? Will it be used for testing surgical equipment or technology? The answer to these questions will lead us to the answer of what “clinically relevant” means on a case-by-case basis.

To give a more specific example: if a customer needs a model for skin tissue, we will work with them to specify what the model needs to do and what it does not need to do. If all the customer needs is a model that provides a visual representation of the different layers and colors of skin tissue without the feel or function of the skin, relevance will be achieved in a much different way than for a customer who needs the tissue to accept an adhesive bandage, surgical staples and includes simulated blood flow.

Additionally, we wouldn’t want to create the same models for these two hypothetical customers because the cost of the first model will be significantly lower than that of the second model. We maximize the model for the function it needs to serve without adding unnecessary costly features that won’t be part of the story the customer wishes to portray with their model.

To bring this discussion all together, the way a model is created is totally dependent on the goal of the customer. The point of what we do is to allow the customer to convey what they need to convey as clearly as possible, not to make a model accurate down to a microscopic level.

We can make a model as “accurate” as necessary for the specific purpose for which it will be used. But through this process, what we’re truly doing is making the model relevant. But isn’t that what you really wanted to know all along?

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then a customized model is worth a million. If all that was necessary to tell the story of your medical device was a general replica of what human anatomy looks like, then a two-dimensional sketch or illustration would do. However, medical practice is hands-on so medical procedure marketing and training are much better served with a hands-on experience.

This storytelling narrative is particularly relevant to medical salespeople and trainers because, without it, their product is just an unknown object. The story is the education, the teachable moment, the preparation for a new procedure. We are grateful to have the privilege of helping depict that story.

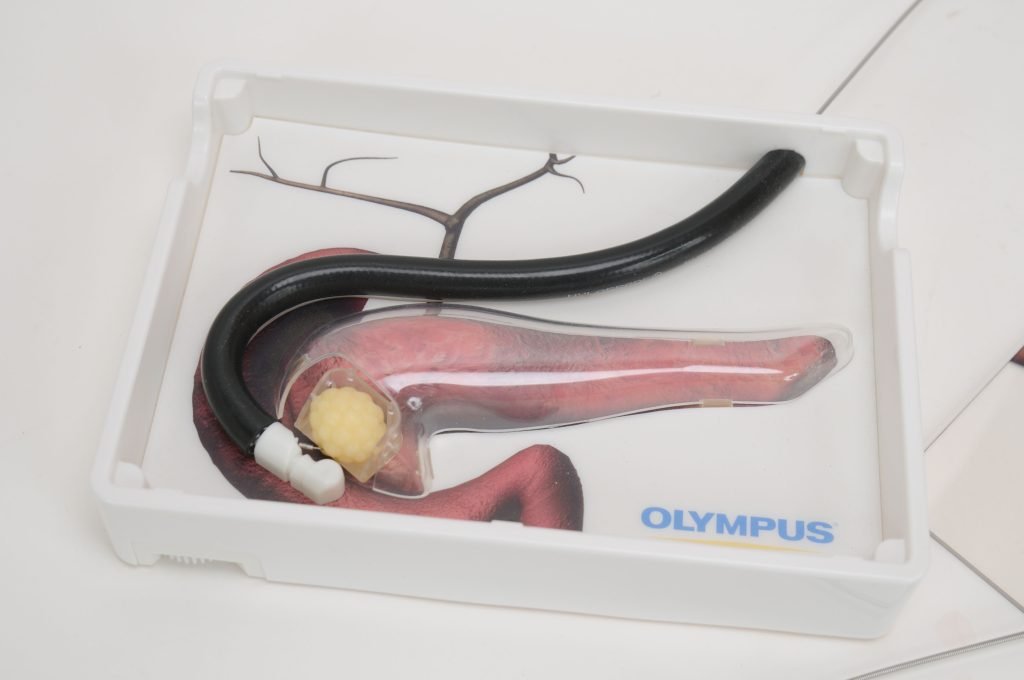

One of the many scenarios in which we helped our clients tell an interesting and important story involved an improved way to biopsy the pancreas for Olympus.

Olympus is best known as a camera company. Their main consumer products are cameras, camera lenses, and audio equipment. Perhaps not coincidentally, at the time of writing this, they have a large banner at the top of their website that says, “TELL YOUR STORY,” bold and all-caps.

This time, instead of Olympus helping customers tell their story, Pulse MDM helped Olympus tell their own story. In addition to their personal cameras, Olympus is a leader in medical scope technology (among other products in their medical division).

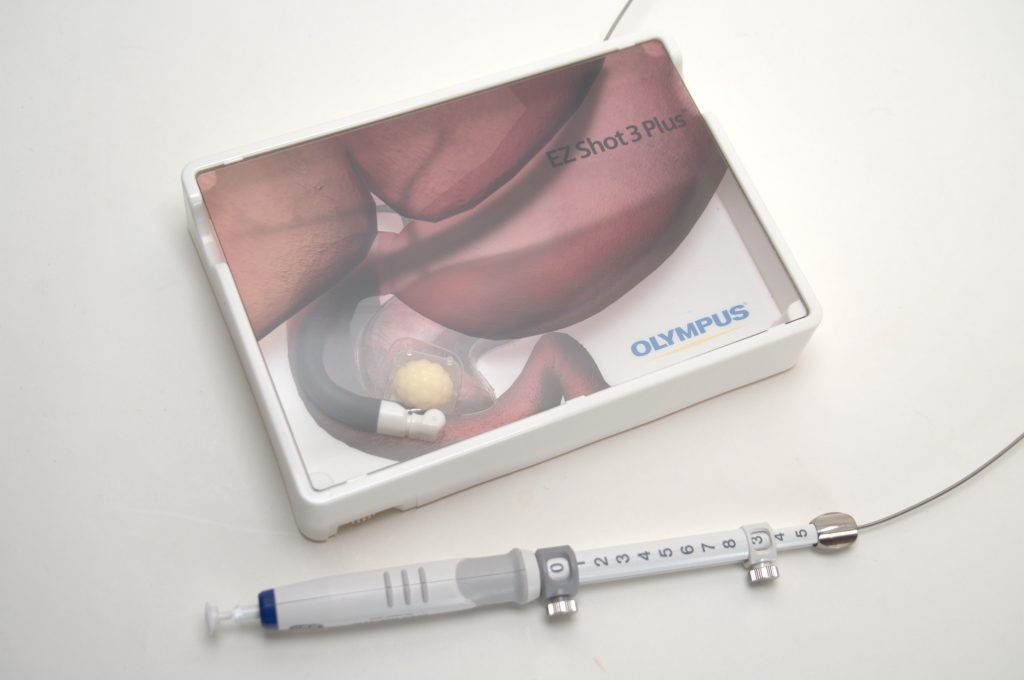

Olympus designed an instrument to use with their ultrasound endoscope for ultrasonically guided fine needle aspiration (FNA).

This instrument is called the EZ Shot 3 Plus, a single-use endoscopic ultrasound needle with advanced puncture-ability that enables tissue penetration from oblique angles, enhanced visibility that ensures accurate lesion targeting, and a flexible and resilient needle that provides unparalleled access to ensure a predictable trajectory, even after multiple passes.

Olympus came to Pulse with the challenge of demonstrating their improved approach to pancreas biopsies.

Pulse worked with Olympus to understand the key differentiators of the EZ Shot 3 Plus. The purpose of the model would be for sales demonstration. It needed to not only demonstrate what the EZ Shot 3 Plus could do, but the ease and efficiency in which it could do it.

From there, Pulse designed a model that would simulate accessing a lesion from difficult endoscopic positions. The model needed to provide an environment that didn’t just prove that the EZ Shot 3 Plus could handle a routine scenario with ease, but rather a scenario that would typically cause surgeons significant difficulty. The model would create a “wow factor” and allow medical salespeople to immediately gain the attention and curiosity of surgeons and decision-makers of medical organizations.

We designed a replaceable lesion at the pancreatic head that would allow the surgeons who trained with the device and model to puncture the lesion and receive tactile feedback comparable to the feedback they experience with a real pancreatic lesion. The model included a durable lesion that could be used indefinitely, as well as a removable cartridge that could be populated with a small tomato or grape for greater tactile accuracy.

To provide clinical context, a flat front panel with a printed translucent stomach and liver was positioned above the biliary tract and pancreas as it is in human anatomy. The demo could be completed by looking through the translucent anatomy or removing the front plate to clearly see the needle penetrate the lesion. Printing anatomy for context on a flat surface is significantly more economical than rendering them as three-dimensional objects and does just as good a job.

In addition to replicating a clinically relevant scenario, Pulse wondered how to reduce the awkward carrying of the cumbersome and expensive ultrasonic endoscope, which is required to demonstrate the procedure.

To address this challenge, Pulse recommended the inclusion of a replica of the last 12 inches of the ultrasound endoscope that could be pre-placed in the correct position to perform the needle biopsy. The scope replica needed to incorporate the moving “elevator” as the mechanism that the physician used to control the trajectory of the needle. Because the proximal end of the scope was removed, the elevator mechanism would be operated using a small thumb wheel at the corner of the model to correctly position the needle.

By using this strategy, we significantly improved the ease and cost of demonstration for the Olympus sales team. The process no longer required the full cumbersome and expensive endoscope and could instead accomplish the same task with the endoscope replica, adding to the model’s durability, transportability, and repeatability, while maintaining the primary focus; that the EZ Shot 3 Plus could handle difficult biopsy scenarios easily.

After the CAD data and prototype was approved and the models were produced in their final form, it was introduced to the field team.

Three hundred units were produced to provide every sales team member around the world with a way to demonstrate the EZ Shot 3 Plus. The compact design of the model provided numerous marketing opportunities for Olympus, as their device could just as easily be demonstrated in a hospital corridor as it could at a tradeshow or conference room. The model provided a way for each member of the sales team, regardless of where they were or who they were speaking with, to tell the same amazing story.

Instead of waiting to fly surgeons in to attend a lab, the model could travel with the salesperson directly to the surgeon and their team. The EZ Shot 3 Plus, and the story it told using this model, was an immediate success.

In fact, one of Olympus’s medical device team’s prospective clients was able to demonstrate the device for the value analysis committee of the hospital organization they were presenting to:

“One of our sales reps was using the new demo model to demonstrate our device to a prospective client. The physician liked how the model communicated the device’s value and unique capabilities so much that he actually took our device with the model to the hospital’s value analysis committee and demonstrated it for them. The committee approved our device and is working on replacing two devices that are currently in use at that facility with our product.” – Olympus Endosurgery Product Manager

This excerpt says it all. The model created the “wow factor” it sought to create and allowed Olympus the ability to portray their crucial product to its full extent. We provide the medium for the stories that will turn the page in medicine.

As with any industry that delivers a customized product to a consumer, several of the most commonly asked questions for developing anatomical models involve pricing.

How much will my model cost?

What determines the price of my model?

Are there ways I can save money on my model while still meeting my specific requirements?

What parts of the process cost the most? Which parts of the process are least expensive?

You get the idea…

The truth is that there are many factors that affect the price of a model. Since our models are designed and created based on the specific needs of our customers, an exact answer cannot be given until we know exactly what is expected.

With that in mind, there are several overarching trends that will affect the cost of an anatomical model regardless of what is needed. These are the top seven factors determining an anatomical model’s price.

Most of what we do involves creating a custom product outlined by a customer’s specific needs. This involves meticulously crafting and prototyping and results in a beautiful and functional finished product.

However, there are circumstances where not every component within a model needs to be customized to produce its desired look, feel, and function. In these situations, stock parts may be a great option to keep costs lower for the customer.

As with most of the custom modeling process, there are various options to reach the desired outcome. Pulse MDM may construct a model entirely with custom parts because that is what’s necessary to satisfy the needs of the training or demonstration. In other instances, only certain components are required to be custom-built, while some of the supporting infrastructures can utilize less costly stock parts.

This type of mixing and matching is a helpful and important advantage that can provide the ideal outcome for customers based on their budget and specifications.

Most of the time, for the purposes of low-volume medical demonstration models, molded parts are more expensive to produce than fabricated parts. We typically mold more complex shapes, and laser cut simple 2-dimensional shapes. Molded parts require a mold, while fabricated parts do not.

Much like the previous example, Pulse MDM may choose to combine 2-dimensional fabricated parts with 3-dimensional molded pieces. For instance, let’s say a customer is looking for an anatomical model of the large intestine with a realistic depiction of a colon polyp for medical demonstration and training purposes. In this case, the customer may not require a fully molded colon, but only show context to help the clinician determine where the polyp is.

This design allows the entire structure of the large intestine created using fabricated (laser-cut) parts and then have only the polyp be a molded 3-dimensional structure. This would allow the customer to get a high-quality model that meets their needs while keeping costs much lower than if the model had been created using all molded parts.

This example is not as obvious. Certain models, like a kidney or a uterus, require creating a cavity within a larger shape. This is accomplished by creating the internal cavity as a male shape in wax. The soft material is cast around the wax, which is melted to leave a cavity behind. This multi-step process produces a beautiful and effective result that is more costly than making the targeted anatomy in 2 halves.

If Pulse MDM determines the demonstration does not require the model to be one continuous structure, the cost of their model can be reduced by having a cavity formed by two separate pieces that fit together. This serves a dual purpose because not only will it bring down costs during the creation process, but it may also enhance the visibility of the inside of the cavity for demonstration and teaching purposes.

As the saying goes, “communication is key.” A perfectly customized anatomical model cannot be created unless we know what perfection means to that customer.

We ask lots of questions before a model is finalized. These questions typically start as “big picture” items, which branch into increasingly specific questions until everyone involved is on the same page. With that in mind, we can only go as far as the information provided.

If a customer is unsure in their responses about the specific details of what they need for their model to be perfect for them, this causes delays and potential miscommunication-driven surprises throughout the production process. These surprises may result in processes needing to be redone, which drives up project costs.

As stated in November’s Ask Allison, one of the amazing advantages of a Pulse MDM made custom anatomical model is that we are able to revise the material recipes until they match the precise color, feel, and function of the customer’s needs. However, if a customer determines later on that they would like a change in the actual dimensions of the model, no matter how small a change, the CAD data needs to be updated, and new molds need to be created, which would also drive up costs.

Factor number six is another one that is easy to imagine. The more parts that need to be produced to make a model, the higher the cost for that model. However, the larger number of models ordered, the lower the unit cost.

High-volume production can often be done in China, which keeps costs down significantly. It’s not always quite so simple, though. The tradeoff for the lower production costs in China is increased time and potential for delays compared to native production. Whether or not this tradeoff is worth it is entirely dependent on the customer’s timeline and preferences.

For certain specialized models, it is imperative that they are water-tight and/or pressure-tight. The good news is this can be done to ensure the model meets the needs of its intended function! However, this does require additional design, production, and testing effort.

In most cases, anatomical models do not need to be water-tight or pressure-tight to meet the specifications of use, so this is a cost that most customers can often avoid.

There are many additional factors affecting the final cost of an anatomical model; these are just seven of the most common. If any of this seems as if it would be overwhelming for our customers, remember that custom model creation is an interactive process that allows us to collaborate with our customers throughout the process to ensure we are asking the right questions to lead to the most cost-effective product while meeting the customer’s exact needs.

The beauty of custom anatomical models is that they can be as simple or intricate as a customer envisions. As outlined throughout the seven factors above, numerous decisions can be discussed to keep prices within a customer’s budget.

However, you need not learn or even understand these principles. Pulse MDM will make these decisions on your behalf for the model that best tells the story of your medical device for the least possible cost.

Humans are incredibly intricate and complex organisms. As you zoom into the individual components that make us human, things seem to get even more complex.

Human tissue is quite literally what holds us together. It is the substance that makes up every component of our bodies. It is what gives us shape and structure internally and externally. It comprises our skin, bones, muscles, organs, nerves…you get the idea.

There are four basic types of human tissue, but within each type, there is a vast array of variability and individuality. For this reason, human tissue was not possible to emulate accurately until relatively recent technological and engineering advances occurred. Today, it is not only possible but necessary.

Replicating human tissue is vital to medical and scientific research and development, as well as demonstration and training. Without these important fields, we can’t move forward with certainty and confidence.

There are essentially two categories of tissue replication: biologic and non-biologic. Biologic tissue replication means that live cells are used. A popular example of this was discussed in a previous Ask Allison article: 3D tissue printing.

3D printing of cells is typically used for regenerative medicine, drug discovery and development, and 3D cell culture. This is a fascinating and truly powerful advancement in medical technology, but it comes with its downfalls. Due to the high cost and fragility of the structures produced with 3D tissue printing, it is not an ideal option for medical demonstration and training.

That brings us to the second category: non-biologic. Non-biologic tissue replication is also commonly referred to as synthetic tissue replication. As the name implies, no live cells are used in this category.

Within the non-biologic category, we can break things down further into the two most common types of synthetic tissue: hydrogels and rubbers.

Without getting more in-depth than you probably care to know, hydrogels are essentially a polymer that doesn’t dissolve in water. Their chemical makeup allows them to be three-dimensional, absorbent, and demonstrate a defined structure (much like native human tissue). This makes them an excellent tool for biomedical purposes, including research and development, but also demonstration and training where a high degree of multi-layer tissue precision is necessary.

Rubbers, on the other hand, are generally more broadly understood because we see and use many types of rubberized substances and objects every day. As you can imagine, based on how widely rubbers are used in so many industries, they provide an easily customizable and moldable medium.

Hydrogels and rubbers each play an important, yet unique, role in the synthetic replication of human tissue. For instance, rubber is ideal for replicating tissues that require specificity in these traits:

Meanwhile, hydrogels are best used for tissues where these properties require a higher degree of specificity:

Due to the complexity of the chemical composition of hydrogels, a polymer scientist is typically involved in the production process. The expertise of polymer scientists allows for a quantitative and scientific level of precision that is not as prevalent during the production of rubbers.

Because of this level of scientific analysis, hydrogel tissue replication is generally more expensive but also provides an enhanced experience in the following areas:

Rubbers also provide excellent customization opportunities and typically rely on more qualitative information. If a customer wants a rubber-based synthetic tissue to look or feel a certain way, the recipe can be infinitely adjusted based on the descriptions provided. Since rubbers do not require the highly quantitative expertise of a polymer scientist, they are generally less expensive while providing the best option for tissues in these areas:

Just because hydrogels and rubbers provide different advantages doesn’t mean they need to be thought about independently of one another. Rubbers and hydrogels can, and often are, used in conjunction to provide an optimal experience. For instance, an entire model can be created using the more cost-effective customized rubbers, but one specific structure within that model can be created using hydrogels. This combination of synthetic materials reveals an endless stream of possibilities.

Many people falsely assume that biologic tissue provides a more “realistic” experience than non-biologic tissue. Due to the downfalls of biologic tissue replication discussed earlier, this is often not the case.

Synthetic tissue replication offers a level of precision and customizability that biologic tissue cannot. Both rubbers and hydrogels can be adjusted to match the targeted tissue properties desired by a customer. This creates infinite opportunities for medical demonstration, training, research, and development.

The primary benefits of utilizing hydrogel and rubber models include:

The beauty and fascinating nature of non-biologic tissue replication come with the convenience and customizability it provides. It’s amazing to think that this advancement that was unimaginable in the not-too-distant past is happening today. Not only can human tissue be replicated, it can be replicated with a level of precision that most didn’t even know was possible.