Medical Device + Model = powerfully distinguish your brand

Imagine being a Medical Device Engineer and you’ve got, let’s say, some sort of catheter. You’ve just had a really novel idea around how it moves through the vascular system. In order to test how it steers & progresses through the vessel, you have cobbled together an initial model that’s made from paper towel tubes, duct tape and coffee stirrers — the very first germ of a model. As you jiggle and twist it about, you are probably wishing that you had the vessels of a right arm that you could pull out of your desk drawer … just to play around with.

We wish you did, too.

Our Med Device clients have actually shown us the FedEx boxes, plumbing parts and fishing gear that they are using. Oh, and apparently fruits & vegetables are in widespread use, too. In fact, beets are very popular. It truly is fantastic (& occasionally hilarious) when a client shows us what they have been using as a model. Because it means we don’t have to convince them about the merits of models. It shows us that they are already half-way there.

The headwinds that face the medical device industry are pretty strong right now in terms of longer, more intensive, more expensive regulatory timeframes. It’s extremely important for early-stage startups and teams working on new devices to ensure that their idea for a device is viable. Prototypes & medical device models regularly come into play in terms of generating interest and exposing a potential idea to the marketplace. So, we’re advocating — practically agitating — that everyone “Think Models” throughout the development cycle of a device. We want to sway you to turn to a model much earlier in the creative process when all you have is simply an idea – with the hopes of helping you get others to jump on board, acquire financing, and gain champions. Of course, much, much later in the process, we want models to also help support all chances to offer hands-on practice with your device, at every opportunity and in every setting.

Let’s start with models that can be used before you reveal your ideas even to your own associates, before you share your ideas within your own team.

You’re thinking of and practicing a new way to extract a stone from a kidney. You have thought through only a quadrant of the idea. It’s an inkling of how it would work, and what that might look like. If you had a model on your table, you would do some tests on the design. You could try your first seed of an idea. Take a first swipe to see — is this even a little bit worthwhile? You would be able to answer your initial question of. “Is this something I want to pursue?”

In using a model the moment an inspiration first hits you, you will immediately discover all sorts of things — uncover faulty assumptions, gain confidence in other areas, change-up some of your original thoughts, and grow your idea into something that you then could bring to others.

“Every time you make a prototype, you learn something. And so the more prototypes you create, try and test, you veritably juice the development cycle.” —Allison Rae

Yes. Juice. Maybe even beet juice.

There will be a point, early on with your prototype, that you will be tempted — or even eager — to go to an animal. But the requirements are stringent. You will have to have something that you can justify to your internal review board – demonstrating that it’s worth going into the lab. With a model, instead of dramatic learning (success or failure) in an animal or a cadaver, you can let some of those weaker ideas fall away. You will cast aside some of your non-workable ideas, discard approaches early and quickly — and likely in the confidence of your own team. And you will find your ultimate direction through each early failure.

Another challenge to the hurdles of taking an idea into the lab is the inconsistency of the animals. The processes to make a prototype model are going to yield the exact same model every single time, whereas if you have eight different animals, then you’re going to get different feedback. The properties will be different on each animal, and it could cause unwanted variables. Eventually you have to address that, but early on you’re trying to eliminate ideas. Using models makes it easier to iterate quickly. You can repeat earlier, less expensively, and definitely with way less paper work. For an accelerated development cycle, models make each try quicker.

Certainly, R&D people understand the merits of using models because they are by nature creative in trying to find solutions. As we said earlier, Pulse sees R&D clients cobbling up their own fixtures or using industrial parts in the place of body parts. But making anatomical models is not what they’re charged to do. What they are charged to do is design the device, and making models becomes a distraction from the main program.

What training and clinical teams are charged to do is educate the physician. Making a model or finding a model also can be a distraction to them. Knowing that models are so very valuable in R&D, you may also consider that you are underusing medical device models in terms of professional education.

A few years ago, members of a Med Device team were kind enough to invite us to one of their training sessions for surgeons. It was a lecture from their physician, and then a porcine lab demonstrating their approach. Labs can be big, cumbersome programs when you consider everything that goes into them: choosing a location and date that does not conflict with other programs, your staff members’ time & commitment to the program, inviting and flying in the surgeons, setting up the lab, navigating through that facility’s or that country’s requirements. The time and dollars involved can make it extremely inconvenient and costly. Obviously, the benefit is that it’s real tissue and a live or life-like situation.

We asked that Med Device team after the lab: “What would you need in order to reduce or to stop doing the porcine labs completely?” Their response: “A way to teach and allow practice, placing and fastening our device in life-like tissue, giving every surgeon a fresh try.”

What we created were portable, insufflatable, laparoscopic trainers with consumable, replaceable, abdominal plates that are actually engineered to accept a large trocar without the model losing pressure. We used the client’s company ports on the sides of the models, and we created non-medical grade scopes that are USB-compatible, so no need for any technology except a laptop. Now their teams take the models to any lab, hospital OR or doctor’s office — even hotel ballrooms. Different than a lab, they have no restrictions culturally anywhere in the world. Unlike a porcine model, it can be stored in a closet, put in the “boot” of a car, and checked as luggage. And the surgeons who are prospective clients are getting hands-on practice with their device & procedure before they are in a surgical setting.

The clinical & training teams found that it multiplied opportunities to engage surgeons in critical conversations.

More chances for critical in-depth conversations are what all of our sales and marketing teams also want.

One client told us; “I always leave physician training courses thinking, ‘I wish I could take that model with me.’ If I could use that model in the field, if surgeons that I meet with could try it, my sales would definitely increase if not go through the roof, because it’s not only a clear way to differentiate my particular device from the competition but it would be a great way to add value from the physician’s perspective.”

And we said; “Exactly!” We are absolutely driven to provide Med Device teams with models to demonstrate their devices. And not every model has to be a complex, realistic anatomical copy.

Some models can be a small slice of the anatomy, only the targeted location for the procedure. When what differentiates the device is not the full procedure, the model can be focused on just the organ or vessel or tract that you need to highlight for your competitive strength. As an example: If the surgeon already knows how to go through the chest wall, and the chest wall is not the focus of your deployment, then the chest wall does not need to be part of the model in order to underscore your key strategic message. By paring down the model to the absolute essence of what you need to show, the model is smaller and more lightweight, takes less materials so is less expensive, and can be designed to be easy to set up, use and reuse.

Giving each salesperson a model that’s designed precisely and engineered intentionally to deliver a very specific experience using your device, dramatically lengthens and deepens the conversation with the physician. And we know that when you add touch to your visual and auditory content, you boost comprehension and recall. Surgeons will be intrigued by the experience and fully engaged with your product.

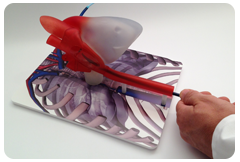

Occasionally, a model can be designed to be sent directly to physicians, literally giving them an experience right at their fingertips.

Client Quote: “The model has accomplished what we had hoped and more. It has helped us to gain a competitive advantage in the realm of safety for patients. Clearly, when patients are exposed to the model, they pick out our soft silicone piece in comparison to the large metal coil every time.”

This model project was for a permanent contraceptive device. Our client was introducing a product that’s a foamed silicone implant about the size of a grain of rice. With bipolar energy to disrupt the surface of the fallopian tube, the soft-foamed silicone is implanted, the tissue grows into it and it’s comfortable & inert. The competitor was making a large coil spring, maybe an inch long, sharp on both sides, and made of metal.

When our client posed the scenario to us, we came up with a number of concepts of how to tell that story with a model — allowing the physician, and eventually the patient, to come to their own conclusion.

The model that was created has a replica of the competitor’s device in the right fallopian tube, and in the left fallopian tube there’s a replica of our client’s device. The model has a lid you can take off and feel the softness of the silicone implant and feel the hard metal of the other. But even just looking at it you can see that there is no way anyone would choose the metal coil over the foamed silicone implant. The exciting part was 13,000 models were sent directly to their targeted surgeons, achieving potential market coverage overnight.

The process of learning is different for everyone. There is usually that period of frustration where you don’t get it, don’t understand it. Then, there is the leap – “Even though I understand it intellectually, actually doing it is proving challenging.” Then, it’s putting it aside. And then finally, “I am really good at this, I want to show it off!” We have clients that tell us about standing-room-only labs where the physicians are absolutely salivating to get a chance to do the procedure and on the other end training classes where physicians are hesitant to try the actual hands-on component because they are around their peers. We have device developers who are frustrated in telling their story to non-medical people because they don’t have a way to make it come alive for their audiences. We know physician educators who understand the power of hands-on experience, but don’t have the ability to put the device in every single surgeon’s hands. And we know that you have a million salespeople who want more and better ways to engage their clients.

If there is one thing we know without a doubt it is: When you match your medical device to a model, demonstrating your product’s advantages while giving surgeons hands-on experience — you powerfully distinguish your brand.